Peter Culshaw

21 Apr 2003

Next month, former band members of the composer and bandoneon-player Astor Piazzolla will perform the music of a man whose greatness is finally being recognised. Peter Culshaw reports.

|

|

|

Although often vilified in his lifetime, in the years since he died in 1992, the Argentinian musician Astor Piazzolla, who invented what he called “new tango”, has become lauded by increasing numbers in the classical world as one of the greatest contemporary composers of the last century.

Celebrated cellist Yo Yo Ma recorded a million-selling Grammy award-winning album of his compositions, The Soul of the Tango, while violinist Gidon Kramer, the Kronos Quartet and Daniel Barenboim among many others have recorded versions of his music. When I met one of America’s leading composers, John Adams, recently, he told me that Piazzolla is one of the few modern composers he considers “one of the greats – he took tango music and elevated it”.

While Piazzolla wrote nearly all his music on a piano, when he performed live, he always played a strange 19th-century German instrument called the bandoneon, a glorified serpent-like squeeze-box on which he became a true virtuoso.

On May 2, the Quinteto Piazzolla, formed by his former band members including guitarist Horacio Malvinino, who played guitar with him from 1954 until his death, perform at the Barbican. The superb bandoneon player Nestor Marconi plays Piazzolla’s parts, and pianist Joanna MacGregor and classically trained accordionist James Crabb make guest appearances.

Born in 1921, Piazzolla was a musical revolutionary. Although based in tango, his music combines elements of jazz and classical styles to create something entirely new. How deadly seriously the Argentines take their traditions of tango, and what Piazzolla was taking on, can be gauged from an editorial in the La Mancha newspaper in 1961: “Piazzolla has dared to defy a traditional establishment greater than the state, greater than the gaucho, greater than soccer. He has dared to challenge the tango.”

Related Articles

30 April 2002: Fizzing fiesta takes tango to exhilarating extremes [review of the Gotan Project]

21 Apr 2003

Malvinino told me when I met up with him in Buenos Aires that, at the height of the hatred towards the new music in the 1960s, he used to receive regular death threats for playing in Piazzolla’s group. “They would ring up and tell me to quit the group or else. Astor had the most trouble, of course.” Some taxis drivers refused payment from the maestro, while others wouldn’t let him in the car, telling him he had “destroyed the tango”, Malvinino recalls. Physical fights between anti- and pro-Piazzolla camps were fairly common. “Fortunately, Astor had been a boxer and knew how to take care of himself, and playing the bandoneon every day gives you strong arms,” says Malvinino. The headstrong Piazzolla did nothing to calm the situation: on one notorious occasion in a TV studio, he ran into a tango singer, Jorge Vidal, whose style he loathed, and a punch-up ensued.

But this was in keeping with tango’s violent and rather sordid past. The dance is said to have originated from the knife-fights of Italian immigrants, and the music was first heard in the bordellos of Buenos Aires in the late 19th century, Malvinino told me: “Just as jazz musicians must swing, tango has to have mugre, dirtiness. [A good tango musician] has to be dirty in their soul.”

The word tango is probably a Bantu word (there are several towns called Tango in Africa), reflecting the rhythms derived from slaves, but the music is much more European and less African-influenced than other Latin music such as samba; all the most famous tangueros have Italian surnames.

Early tangos were played with accordions, but these were quickly replaced by the bandoneon, an instrument “much more capable of reflecting the melancholy and nostalgia for the Italians who missed the mother country”, according to Piazzolla’s biographer, Maria Susanna Azzi.

Despite its origins, by the 1920s tango had been embraced by European high society, and had become the national music of Argentina. It was in this chauvinistic context that Piazzolla’s tango revolution seemed so shocking.

He had an unusual background for a tanguero. Although he was born in Mar del Plata, he was brought up from the age of four on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where his father was a barber. The Italian quarter was next to a Jewish area, and it’s been suggested that the rhythms of Piazzolla’s music (which he called “oriental”) are very similar to Yiddish music.

In the 1940s, Piazzolla played with the famous tango group of Anibal Troilo, before forming his own band in the 1950s. But he was always interested in all kinds of music. He had a picture of Bartók on his desk, and loved Stravinsky.

A key moment in his musical life was when he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger in the late 1950s (whose influence on 20th-century composition was enormous – having taught Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson and Philip Glass, among many others). He told his daughter, Diana: “She helped me find myself”.

Perhaps because of his radicalism, it was only when he was in his sixties in the 1980s that Piazzolla made a good living from his music (the Jamaican singer Grace Jones had a hit with a cover of his Litertango) and he became celebrated, especially in France and Italy. I saw him play a couple of memorable concerts for a small audience at the Almeida Theatre in the 1980s.

It was also in the 1980s that Piazzolla produced some of his best records, such as Tango: Zero Hour (Piazzolla’s own favourite), a brilliantly produced record that captures the true spirit of his music in all its complex shades of playfulness and dark melancholy.

The closest parallel to Piazzolla’s tango revolution might be what Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie did with jazz. Like be-bop, the nuevo tango was accused of being intellectual, and you couldn’t dance very easily to it. Piazzolla was also determined to change the imagery of tango; it was time to get rid of the old stereotypes – “the street lamp, the neckerchief, the dagger, the sterile moanings”.

His compositions could be about madmen or the Great Wall of China, about Michelangelo or personal subjects, such as the tender Adios Nonino, perhaps his most famous piece, written the day he heard of his father’s death.

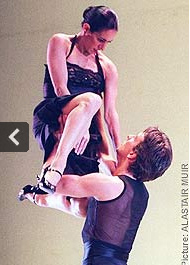

Piazzolla’s music is currently going from strength to strength. His compositions are now accepted in the concert halls, and many dance companies have used his idiom, including Ballet Argentino, a company founded by the Argentinian Julio Bocca. They had great success with Piazzolla Tango Vivo, a fusion tango piece.

While Piazzolla’s own attempts to mix electronics into his compositions in the 1970s didn’t really come off, new attempts such as the Bajafondo Tangoclub, and the young generation of musical post-tango mavericks in Buenos Aires, are more successful.

One of the most popular world music records of the past year has been the Gotan Project, currently touring Britain, who have created a delicious electro-tango concoction.

The tango clubs in Buenos Aires are full again of young and old every night: the music is fashionable once more. And finally, and almost universally, Argentina has recognised the genius of of a wayward son, Astor Piazzolla.

Quinteto Piazzolla play at London’s Barbican Centre on May 2; the Gotan Project tours until May 5.

‘Le Grand Tango: The Life and Music Of Astor Piazzolla’ by Maria Suzannu Azzi and Simon Collier is published by the Oxford University Press at £20.

Referencia: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandjazzmusic/3593098/Father-of-the-tango-revolution.html